Part 26 - 'Portrait Of A Lady On Fire' Is A Sizzling Ode To Femininity, Art And Same-Sex Love

Where did the artistry lie in Portrait Of A Lady On Fire?

I’ve always considered myself to be a romantic soul. I write poetry in my spare time, I read Romantic literature, I often consume alternative love songs. And, as you will know, many of my favourite films are romance-led. I could spend hours talking to you about Mia and Sebastian, Christian and Satine, Mr Darcy and Elizabeth. I am always struck by how distinct each love story is. Each one will be a different shade, a different tone. But, they are all recognisable by the feeling they give the viewer. That soft, melting core like the caramel at a sweet’s center.

I am always compelled by the development of romance on screen. It is true that, when you are in love, it feels entirely your own emotion. No one has ever experienced the intense sweetness you feel, nothing comes close. You feel as if the bond you have with your person is shared by no other couple. You feel as if you are inventing something sacred, with brand new colours and brand new words. Weaving untraced patterns with your fingertips. It is marvelous to see this replicated by cinema.

A friend of mine had asked which film was next on my list. He has asked me what I was essentially going to treat myself to, as he knew of my recent slew of one star films. I had heard of Portrait Of A Lady On Fire’s (POALOF) greatness, which was further confirmed by him. And, when I reached this film’s end, I definitely felt as though I had been treated. With roots lying in Greek myth, poetry and artistry, I came away, flushed with its beauty and emotive nature. And, I can say for sure that this is another love story that will be tangled in my fingers for a long time to come.

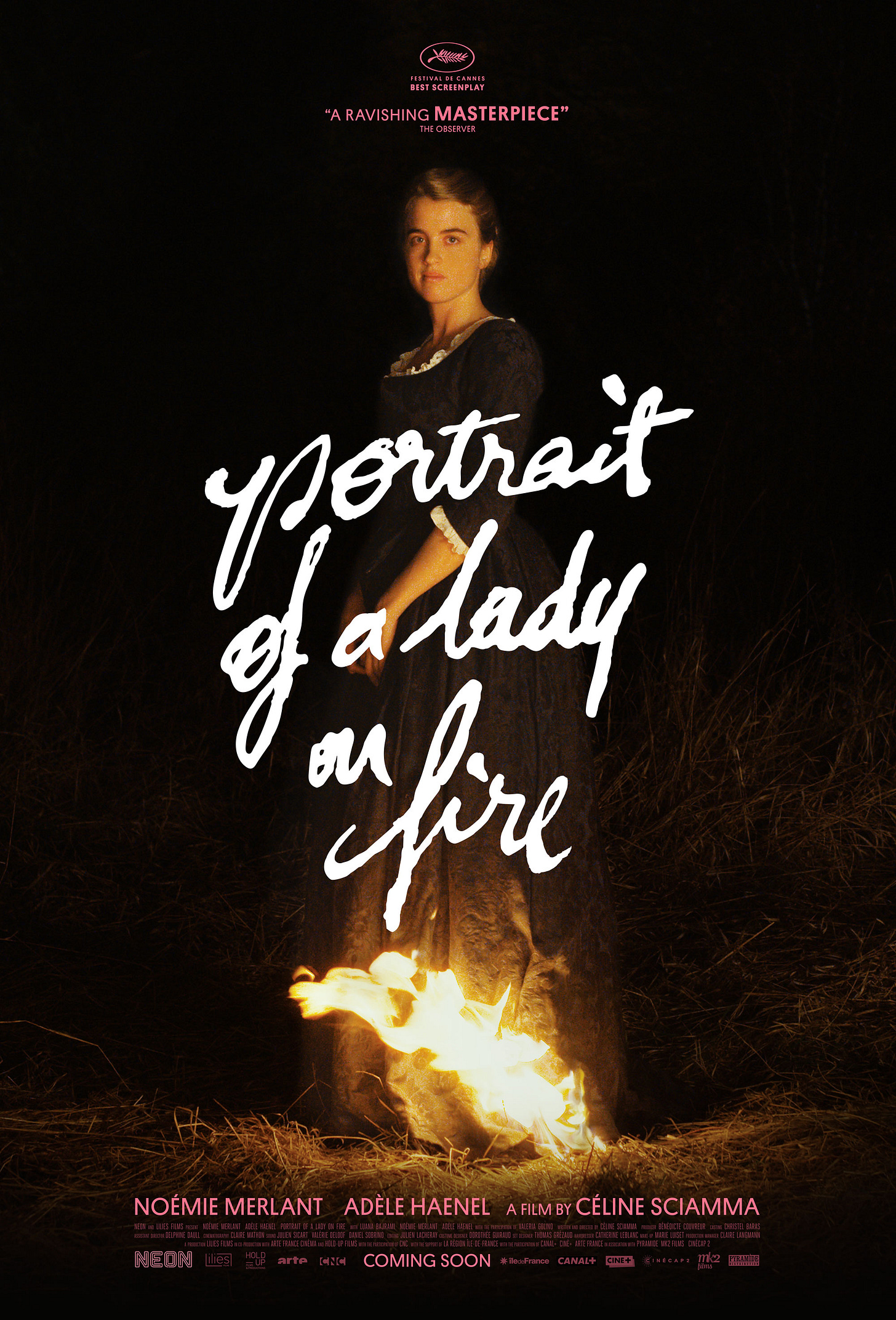

Portrait Of A Lady On Fire (2019), directed by Céline Sciamma, tells the story of Marianne (played by Noémie Merlant) and Héloïse (Adèle Haenel.) Set in France, 1770, we meet Marianne, a painter who is travelling to make a portrait of Héloïse. Her mother, The Countess, has commissioned this. It is to be sent off to a Milanese gentleman, who wishes to marry her daughter. However, The Countess explains that Marianne must not reveal to Héloïse that she is a painter. This is because Héloïse has refused to sit for any painters, as she does not wish to marry a man she doesn’t know. Marianne must pose as a companion for Héloïse’s walks, but use that time to study her so that she paint her in secret. However, Marianne and Héloïse begin to grow accustomed to each other’s company. So, how will Marianne and Héloïse’s feelings develop? Will Marianne be able to keep her secret and complete a portrait of Héloïse?

This film felt as sweet and seductive as a kiss on the neck. There was a tender artistry within it, a kindling sense of passion and devotion. The cinematography was clear-cut, often making use of static shots or slow movements. Director Sciamma wants us to drink this film in, she wants us to move at an unhurried pace. I found myself moving very softly and leisurely after watching, basking in the effervescence that my surroundings afforded. It felt somewhat akin to a gift, to be afforded this slowing down of time. What allowed us to drink this in to a greater degree was the lack of a score. We are treated to a backdrop of silence, occasionally relying on the sounds of nature. It allows us to focus on the attention to detail and to rely solely on the natural connection between the women. The static shots resembled oil paintings, as if they were thick strokes from a paintbrush. It felt as defined as a diamond, as fluid as liquid. The scenery was painted onto the room around me.

Sciamma’s thematic detailing was captivating. I felt as though I were studying a novel, back in my A-Level English Literature days. I wanted to peel back the layers, identify the symbolism with annotations, revel in its secret meaning. There was a strong sense of opposition throughout the film. On the surface, there are very clear divides between the central women. However, if you look beyond this, there is a very clear duality in the painting and the painted. We watched the women’s connection deepen as the painting grows in its vitality. The nature-oriented opposition is truly evocative of the moors of Wuthering Heights. The silence: the stilted tension as they hide their passion. The waves: the roaring adoration when they can embrace the flame.

The performances blended seamlessly and effortlessly, like watercolour. Noémie Merlant thrives as Marianne, convincing us of her passion for painting with a discerning eye and flitting hand. She is very much the Orpheus of the story; an artiste, forever cursed to never look back, never pursue her desire. Merlant bestows little flecks of gold upon this film, each time Marianne’s guarded persona falters. Adèle Haenel’s Hèloïse is stubborn and daring, as she frequently courts the peril their intimacy affords. As the Eurydice figure, she is forever asking Marianne to turn around, to see her and her predicament. To accept her and to grant her her desires. Together, the two harmonise, rising and falling in a wonderfully palatable dance. The minimal dialogue enhanced this, dripping like poetry from their mouths.

Their emotionally chemistry is what we are first directed to look at, as Marianne attempts to crack Hèloïse’s porcelain surface. However, their physical chemistry was something I was impressed by. Nudity is such a contentious topic within cinema; women have been forcibly prodded and posed by the masculine hand for far too long. Female nudity is rarely there to enhance the woman’s femininity. It is often jarring, splashed onto a screen to illicit shock and arousal. However, this was elegant and full of a longing tension. From Marianne drying herself before the fire, to the two women laying in bed together. It seemed to worship the female figure, the curve of the collarbone, the slope of a shoulder. There was a timeless sense of devotion between these two women. It was a deliciously slow burn, something I longed for when I watched Brokeback Mountain.

There were several narrative choices that detracted from the film’s magnificence slightly. Hèloïse’s maid, Sophie (Luàna Bajrami), provides an additional story that slightly cut into the main romance plot. Her story was extraordinarily powerful; she discovers she is pregnant, so both Hèloïse and Marianne take her to have an abortion. I would like to take a moment to credit the director, for choosing to depict this with s positive lens. This is another topic that has time and time again been mistreated; it is shown as sort of secret sin or degrading shame a woman must bear. As Sophie lies down to have the abortion, a baby lies next to her and touches her face. The camera does not shy away from Sophie but we are not witnessing something cruel. It is empowering and yet soft. However, as touching as this was to witness, I definitely think the focus should have remained on the couple themselves. It felt as though it was clashing with their story arc.

Another minor issue came from the beginning and ending. I think there was a degree of messiness; there are a myriad of ideas but they seem to stack and pile, instead of flow. The ending, which is designed to devastate and rip, seems to throw everything at you but the proverbial kitchen sink. It becomes simply too much and there is no room for your emotions to settle. So, when taking all of this into account, POALOF has received a 4 1/2 out of 5.

I feel like I could have flooded this blog post with the things I admired about this film. I mean, I kind of have already. But there are just so many details that tickled me. I think loving English Literature means I was guaranteed to love this film. As well as being a silly little romantic soul. I think there is something to be learnt from Marianne and Hèloïse. It is to embrace the fire. It is to perhaps take that risk and let that emotion trickle through. It is to write yourself in poetry, even if you do not believe the words yet. Trace new patterns with your finger tips. Turn back and look behind you. What do you see? Are you ready to embrace it? Are you prepared to enfold what you desire? Can you bear the weight of its disappearance? I think Hèloïse says it best:

‘Do all lovers feel like they’re inventing something?’

BellaWatchesFilms