Part 14 - 'Detachment' Is A Misery Circus That Ponderously Parades Egregious Stereotypes

Does tackling a myriad of layered and complex subjects in a film ever work fluently?

I know each and everyone of us are occasionally partial to a classic bit of melancholy-soaked media. Whether to indulge some melodramatic whim or to unearth some unresolved emotion - we all need to consume a reflection of sadness sometimes. I am a person that is prone to bafflement when it comes to my own emotions. I don’t understand what it is I’m feeling on a certain day and then I struggle to self-regulate. I then discovered that, aside from being an excellent medium for distraction or for joy, films are an incredibly powerful tool that can be utilised for self reflection. I can think of many examples of where this particular brand of sorrow could be used in that way, including Aftersun, La La Land, Her, The Banshees of Inisherin and Dead Poet’s Society. All of these left me rooted to my seat, awash with the knowledge that, in that moment, I couldn’t move from my seat. I couldn’t go on with my life, my normal routine. Some inner chord had been struck, something had been reset, something had been unlocked with a resounding click.

So, I’ve established the criteria that is essential for films with a certain affinity for misery. Hold onto this because I will be referring to this as I discuss our film of today: Detachment. I was initially going to avoid this film, for the trivial reason that I had seen it many times on TikTok, above some gameplay of a random app. This, for those who are unsure, is usually the hallmark for a bad movie. I had noticed that Adrien Brody, former alum of the school of Wes Anderson, had the starring role in this film. I was intrigued by this, just because of how life-changing the Darjeeling Limited had been for me (of which he was a significant part) He’s also a bit of a celebrity crush of mine, so naturally I had some inclination to watch it. A follower of mine then recommended it to me and I then thought I’d give it a proper go. And, let me just say now, it was not the film I had anticipated it to be at all.

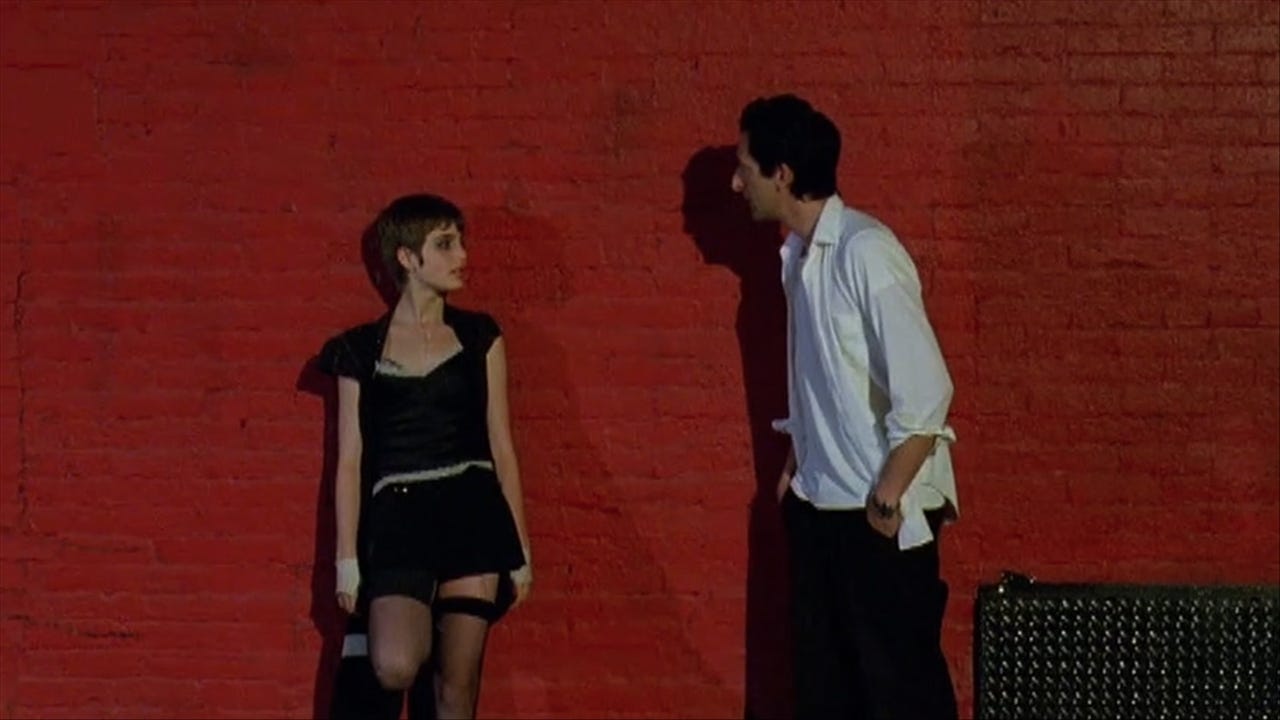

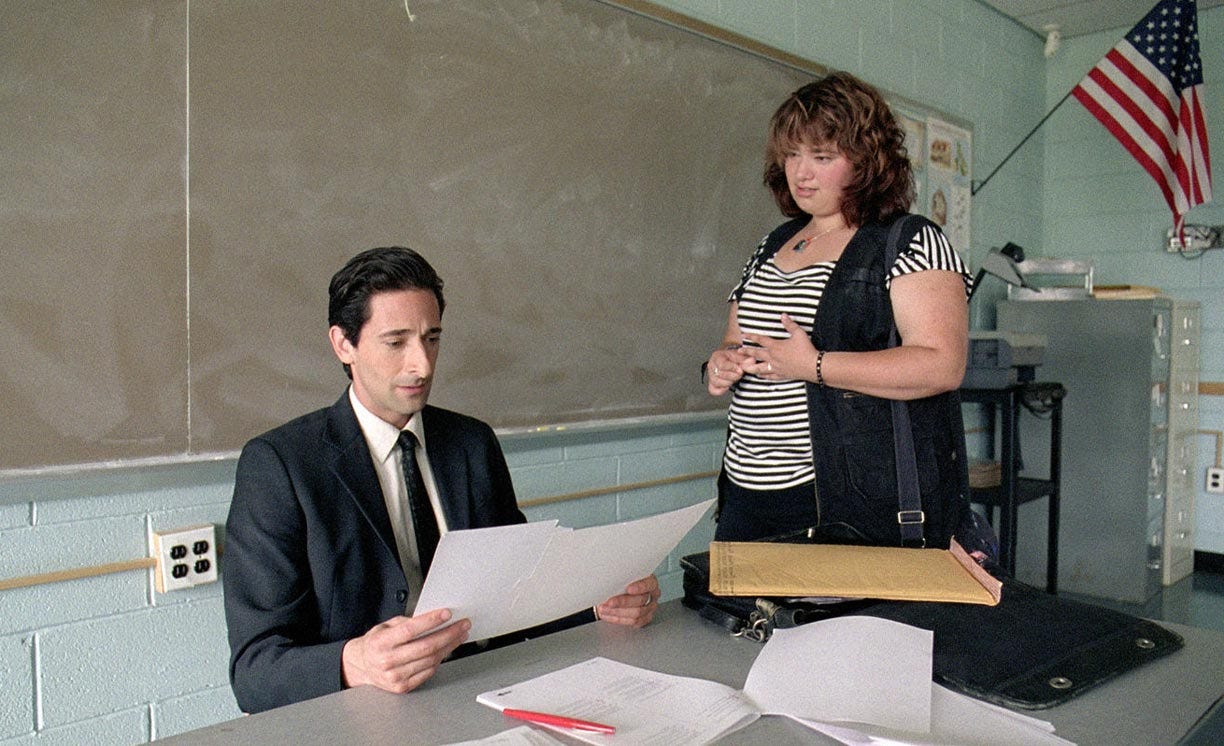

Detachment (2012), directed by Tony Kaye, circulates itself around the life of the tortured Henry Barthes (played by Adrien Brody) He is a substitute teacher who, perhaps as a result of his constant relocation, prides himself on his dismissal of any sort of emotional connection to anything. A solemn and despondent Henry then finds work at a public school, one that seems tethered to the very depths of hell. The students are a rampant mob of rebellious heathens, their parents are perhaps worse; inflexible to the point of madness and desperate to clutch at the belief that it is the system that is failing their children. The weighty combination of these two pressures have forced the teachers of the school into a heavy, burnt-out state of resignation. Whilst Henry is there, however, the most troubled of students seem to gravitate and anchor towards him. So, whilst he deals with this responsibility, he must also manage the welfare of his dying grandfather and the welfare of a teenage prostitute (played by Sami Gayle) he has taken home to care for. By the film’s end, will Henry be able to navigate the delicate balancing act of responsibilities and manage to keep his emotions tethered?

I would like to say that, before I continue this review, I will be touching on the significantly dark themes that arise from this film (namely: suicide and sexual abuse) So, if you are sensitive towards these topics, I would refrain from reading now.

This movie essentially boils down to one inherent issue: it is desperately trying to be something that it is not. It it clawing at this romanticised, melancholic noir-esque drapery but if you peer under the decorations, it is far from sweet, sorrowful ecstasy. Because, and I’m going to be quite frank here, this film was very depressing but it was so obvious in its messaging. It attempts to cover a multitude of deeply disturbing and sorrowful topics but it becomes murky, confused and ponderous. We are wandering from moment to moment with no room to breathe, no time to reflect or understand the implications or hidden meanings. But, as we float drearily from place to place, director Kaye seems to cry out “Life is so horrible! All of these people are horrible or lost or depressed or just generally unhappy! And we have to show you this, again and again, with no nuanced moments of some other kind of emotion!” There is absolutely no versatility in its emotional range which is such a shame because a shift in tone may have worked to enhance or separate the continuous moroseness.

The viewer is left increasingly less attached to the story as the direction becomes far too scattered and confused. We have these flashback moments, then chalkboard drawings, then moments of intense closeups. Perhaps worst of all were the documentary scenes, where we watch an uncomfortable close Adrien Brody seemingly announce the next act with a vague, self-pitying line. Despite his performance being layered, he did not save this film, especially not in these documentary sequences. I felt as though I was suddenly witnessing a divide; there was Henry Barthes and then there was Adrien Brody. The dialogue, coupled with these directive decisions, continued to weaken this film further. There are these sudden drops of intensity, which is so easily a gateway to unreality. For instance, a teacher screaming at a girl, telling her that all she is destined for is the life of a whore. Again, just why was this necessary?

I was surprised and rather agog to find myself physically repulsed by this film. Despite championing a range of ‘emotionally-complex’ characters, they are made flimsy by one-dimensional stereotypes. It left a bad taste in my mouth, seeing the few black characters rooted only in aggression, which is unmatched by any of the white characters. Or, take the ending. The overweight girl of Henry’s class - she kills herself by eating a cake. I genuinely lost it at this point. What the hell was I watching?

Something that particularly snagged my attention was the portrayal of women. From a teenage prostitute who wants nothing more than to sleep with Adrien Brody, to the female teacher who he takes on a date and whose speech blocked out as he is somewhere else, to the overweight girl in his class who is desperate for his attention. Even down to the snapshots of his dead mother who died from an overdose, which contemptuously boasts a gratuitous shot of her breasts. Or the moment where he pushes back the child prostitute’s skirt to touch her thighs, that have been mutilated. Women are reduced to a mere tool by this film and it sickened me. Henry tries desperately to save them all, all whilst caring for his grandfather who allegedly sexually assaulted his mother when she was a child. Which he knew about, when caring for him. Perhaps Henry isn’t supposed to be the good guy. But his portrayal as this saviour of the lost or abused, particularly of women, was frankly disturbing. Especially as they try to juxtapose the relationship between himself and Erica with shots of a young Henry and his mother.

However, hidden deep within the shallow, empty moans of this misery-porn are several intriguing ideas. Droplets of emotion are eloquently dispensed in the form of quotes, which bestow little echoes of realism here and there. For instance, within the first minute of the film, I was touched by the poignancy of the quote which reads as follows: “And never have I felt so deeply at one and the same so detached from myself and so present in the world” Straight of the cuff, we have an excellent call-back to the title, a theme which underlines this film but never escapes it. In fact, the final sequence was an excellent portrayal of detachment, of derealisation. Henry reads out a poem by Poe but the classroom is no longer full with students but with the unwelcome presence of autumn leaves and discarded papers. We see the world through his eyes for a pure, brief second and it is desolate. He has not managed to attach himself back to the world, to his emotional state.

The acting was consistent in the main performers, despite the superficiality of the film itself. Sami Gayle should also be commended for her portrayal of Erica, especially in the breakdown of her connection to Henry. He has called a service to take her into care and in a frighteningly hard-to-watch moment, she is dragged away as she screams pleas for Henry to keep her by his side. There was a tenderness to their relationship but this was still overshadowed by the major red-flags that stood in the way. So, when considering the 1 hour 40 minute slog through this film, I can only reach the conclusion that this should be given a 2/5 stars.

I felt like I needed some sort of dessert or trivial refreshment after watching this film. I need a warm drink or a blanket or at the very least, a better, happier film lined up next. Or maybe even just a hug. Because, as I mentioned earlier, tackling depressing topics such as these should be done with a humane touch, with waves and brush strokes of softness and brutality. Detachment simply tackles too many things and places no reality, no true sense of emotion or sentimentality in it. Where other films have succeeded is within their excellent use of peaks and valleys because, believe it or not, life is not one heart-stopping, world-ending event after another. This film perhaps wants to convince you otherwise, which is to its detriment. But true sorrow lies in its deceiving disappearances, as much as its presence. Nice try, Detachment.

BellaWatchesFilms.

Kind of want to watch it now you have told me how much you disliked it!